What is OAuth?

Since the beginning of distributed personal computer networks, one of the toughest computer security nuts to crack has been to provide a seamless, single sign-on (SSO) access experience among multiple computers, each of which require unrelated logon accounts to access their services and content. Although still not fully realized across the entire internet, myriad, completely unrelated websites can now be accessed using a single physical sign-on. You can use your password, phone, digital certificate, biometric identity, two-factor authentication (2FA) or multi-factor authentication (MFA) SSO solution to log onto one place, and not have to put in another access credential all day to access a bunch of others. We have OAuth to thank for much of it.

OAuth definition

OAuth is an open-standard authorization protocol or framework that describes how unrelated servers and services can safely allow authenticated access to their assets without actually sharing the initial, related, single logon credential. In authentication parlance, this is known as secure, third-party, user-agent, delegated authorization.

OAuth history

Created and strongly supported from the start by Twitter, Google and other companies, OAuth was released as an open standard in 2010 as RFC 5849, and quickly became widely adopted. Over the next two years, it underwent substantial revision, and version 2.0 of OAuth, was released in 2012 as RFC 6749. Even though version 2.0 was widely criticized for multiple reasons covered below, it gained even more popularity. Today, you can add Amazon, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Netflix, Paypal and a list of other internet who’s-whos as adopters.

OAuth explained

When trying to understand OAuth, it can be helpful to remember that OAuth scenarios almost always represent two unrelated sites or services trying to accomplish something on behalf of users or their software. All three have to work together involving multiple approvals for the completed transaction to get authorized.

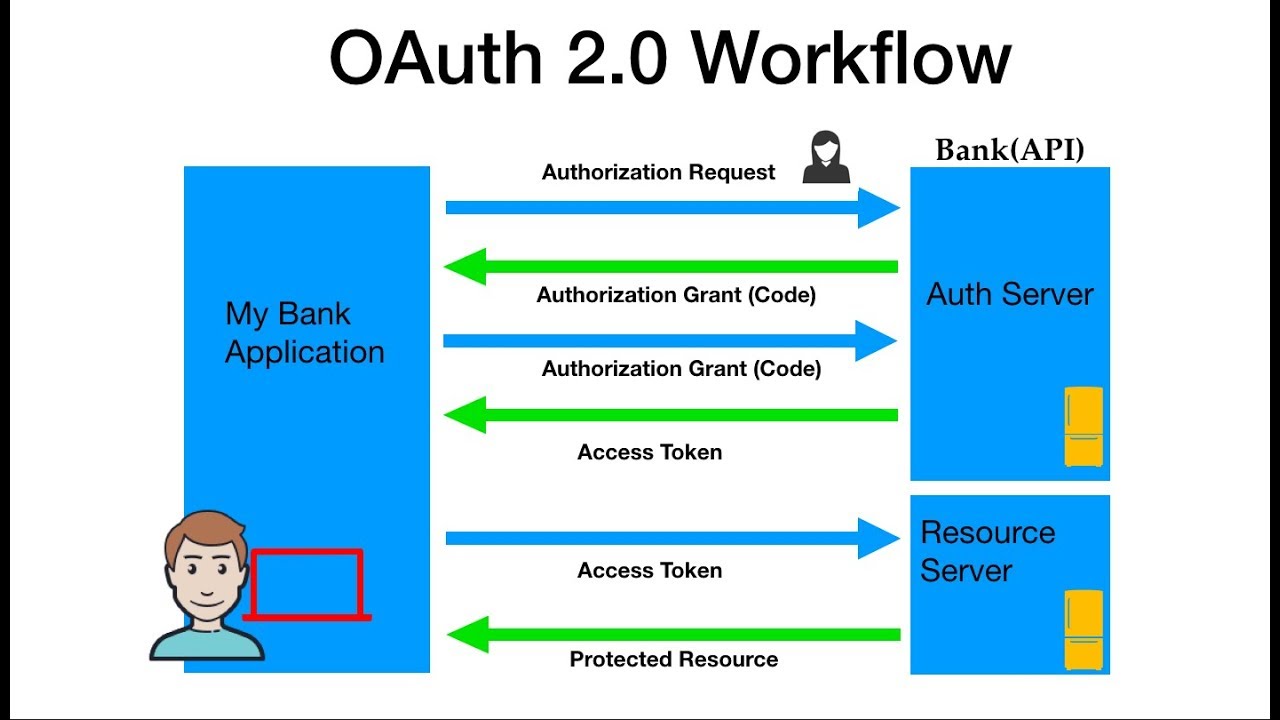

How OAuth works

Let’s assume a user has already signed into one website or service (OAuth only works using HTTPS). The user then initiates a feature/transaction that needs to access another unrelated site or service. The following happens (greatly simplified):

-

The first website connects to the second website on behalf of the user, using OAuth, providing the user’s verified identity.

-

The second site generates a one-time token and a one-time secret unique to the transaction and parties involved.

-

The first site gives this token and secret to the initiating user’s client software.

-

The client’s software presents the request token and secret to their authorization provider (which may or may not be the second site).

-

If not already authenticated to the authorization provider, the client may be asked to authenticate. After authentication, the client is asked to approve the authorization transaction to the second website.

-

The user approves (or their software silently approves) a particular transaction type at the first website.

-

The user is given an approved access token (notice it’s no longer a request token).

-

The user gives the approved access token to the first website.

-

The first website gives the access token to the second website as proof of authentication on behalf of the user.

-

The second website lets the first website access their site on behalf of the user.

-

The user sees a successfully completed transaction occurring.

-

OAuth is not the first authentication/authorization system to work this way on behalf of the end-user. In fact, many authentication systems, notably Kerberos, work similarly. What is special about OAuth is its ability to work across the web and its wide adoption. It succeeded with adoption rates where previous attempts failed (for various reasons).